Despite the passion for everything related to Egypt, its pyramids, and its mythical pharaohs that had been fueling people’s curiosity for years, in 1922 an unprecedented event occurred that not only catapulted the passion for Egyptology but also propelled a spectacular artistic movement, with Art Deco as its main exponent. In a sense, we owe the Empire State’s design to the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun and the mummy that rested there.

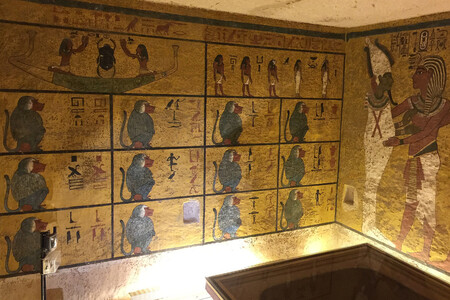

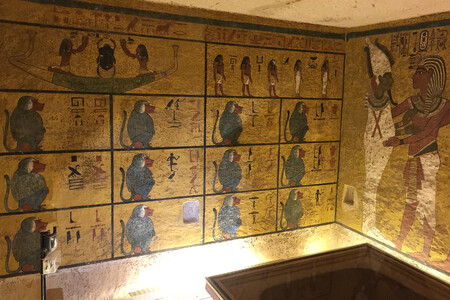

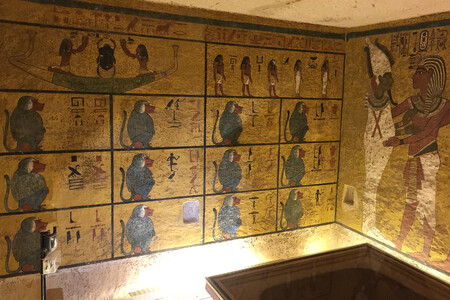

Died at just 18 years old for reasons that are still debated among the scientific community to this day, the mausoleum where Tutankhamun was supposed to be laid to rest was not completed on time, and he had to be reburied in a smaller tomb that became a sort of Holy Grail of Egyptian archaeology. When the expedition led by the Egyptologist Howard Carter found the tomb, his mummy, and the over 5,000 treasures found there, the news spread worldwide.

The Discovery of Tutankhamun’s Tomb

Tutankhamun’s mask, probably the most famous Egyptian object in history after the pyramids, became a symbol of Egyptology and fueled a passion for archaeology and mysticism that only needed a small spark to further ignite that explosion, the news of the mummy’s curse that had caused the death of several explorers who entered that tomb.

Discovered in the Valley of the Kings in November 1922, the first case related to the mummy’s curse was reported by The New York Times, stating that a cobra, symbolizing the power of Egyptian kings and appearing crowning the mask of Tutankhamun, had entered the home of one of Carter’s team members and eaten his canary on the same day the tomb was opened.

A few months after the incident, it was announced that George Herbert, the aristocrat who had financed the excavation and was present the day Tutankhamun’s resting place was discovered, died due to a mosquito bite that apparently became infected affecting his blood. To this, seven other deaths directly related to Tutankhamun’s curse were added, creating a media circus where for months nothing else was talked about.

It was said that they found a dark book warning those who dared to open the tomb, that one of the explorers burst into laughter after the first person entered the tomb saying “I give him six weeks of life,” and with the announcement that Mussolini’s fear of a curse had led him to get rid of an Egyptian mummy he had been given, the conspiracy was complete. For those who lived through that era, the mummy’s curse had provided necessary evidence to take the message seriously.

The Scientific Response to the Mummy’s Curse

However, if it was so powerful, it did not prove to be because even Howard Carter himself, along with 50 other people who were there on the day of the excavation, lived their lives without issues, and even died of natural causes many years later. Only a message from Carter, who wrote in his diary how in 1926 he came across a jackal that reminded him of the god Anubis, even though he had never seen one after 35 years of working in the desert, helped to reignite that flame.

Furthermore, neither Carter nor the team ever believed in the mummy’s curse and remained skeptical of a problem, that of archaeologists dying in strange circumstances after opening a tomb, which did not stop after the discovery of Tutankhamun’s mummy. The most notable case, which helped provide some explanation to those isolated cases, occurred in 1973 when the tomb of Casimir IV Jagiellon was opened in Poland. It was then that, of the team of 12 people who carried out the opening, 10 of them died prematurely.

The explanation they found then, and the one they have tied to similar cases around the globe, is the Aspergillus flavus, a type of fungus found in the tomb that produces toxic spores for mammals, mainly affecting the liver and causing an unusual risk of cancer cell proliferation.

Although not all of the scientific community agrees to link that case to Tutankhamun’s tomb, it could well be the most sensible explanation, along with sensationalism, that we could extract from this whole story. In any case, it came too late because, in the midst of Egyptology fever, Universal shaped the film The Mummy in 1932, and four sequels that continued to fuel the monster myth until its grand return, to the applause of monster and adventure lovers, with Brendan Fraser and Rachel Weisz in the 1999 film The Mummy and its sequels.

In 3DJuegos | The Egyptian pyramids in Antarctica are not man-made, they are actually a phenomenon called a nunatak

In 3DJuegos | The great mystery of the Pyramids has been solved. Science has shown in the Pyramid of Djoser that the correct theory was hydraulic.